Bradford Research School: Disciplinary Literacy: Vocabulary in subject disciplines

Posted 3rd July 2023

In our first two blogs in this series, we have emphasised the fact that generic strategies, although useful, are not always sufficient to fully make sense of subject disciplines. Each subject has its own unique language, ways of knowing, doing, and communicating – ways of thinking. For example, reading in subject disciplines goes beyond generic reading strategies.

In this blog we’ll look at vocabulary in subject disciplines.

There are generic approaches to teaching vocabulary that can work, such as this list from Michael F Graves in The Vocabulary Book:

- Include both definitional and contextual information

- Involve students in active and deep processing of the world

- Provide students with multiple exposures to the word

- Review, rehearse and remind students about the word in various contexts over time

- Involve students in discussion of the word’s meaning

These can work as general advice, but every aspect will look different depending on the subject and the context. And when we really think about our subjects, we can see vocabulary in a different way.

Take that first bullet point. Even the idea of a definitional meaning can be challenged. In some subjects, such as science, that may be the case. But in others, the definition of a word is often contested by scholars. Sometimes words are literal, other times metaphorical. Sometimes they are concrete, sometimes abstract.

Where words come from

Shanahan and Shanahan (2012) share this example of vocabulary in science:

For example, an examination of the earlier presented science vocabulary terms reveals that the list is rife with words constructed from Greek and Latin roots. This structure is not unique to science words, of course, because most English words have such roots. Because science uses such words extensively and for a purpose, however, analysing the Greek and Latin derivatives can provide particularly effective support in understanding science concepts. The purpose of constructing (and analysing) words in this way is to offer a more complete and precise description of concepts than is possible with vernacular terms. Furthermore, such words are considered more resistant to meaning changes and to the morphological shifts that occur across time and across languages.

Contrast this with some of the vocabulary used in history. Try and work out what the Renaissance was just from the word, and you would struggle.

A good activity for subject teams is to look at those glossaries you have built of the vocabulary that you want pupils to learn. What are the patterns? How are the words created? Where do they come from? How have they changed?

I had a look at some glossaries for Music at KS2. Here are some of the things I noticed:

Neo Soul; Motown; Blues; Jazz; Urban Gospel: Here we have capitalisation, and genres of music that bring with them historical origins, cultural significance, contemporary connotations, change of definitions through time, definitional disagreements.

Improvise; tempo; ostinato; unison: These are Latinate words, which raises the question of why? Some internet searching tells me about musical notation being invented in Italy, and many composers were Italian.

Timbre; ensemble: French words. I’ll stop there if only to not spend another hour on the internet. But you get the idea that the words in our subjects have their own unique patterns. What do they look like in yours?

Understanding unfamiliar words

Once again, there are useful generic strategies to encourage pupils to use, such as etymology, contextual clues, and even looking up in the dictionary. But it’s also worth asking what a specific subject strategy would be? And this is where you can ask what an expert might do.

I love Shakespeare, but I don’t always understand every word. So how do I work things out?

Often, I don’t worry about individual words. If I come across one, I ask whether I really need to know this to make sense of the scene or the sentiment. Often I don’t. But I also don’t only use the language on the page to make sense of it. I may have seen the play, or I could actually be watching the play, so I can use contextual cues from the body language, tone etc. The other thing I know is that anything I don’t understand probably has a footnote, so knowing how to navigate these footnotes is important. When I encountered ‘bat-fowling’* in the Tempest, I knew to look across at the line number then find 185 in the footnotes. Other editions have the glossary parallel to the text.

Lots of texts have ‘in-built’ methods of understanding unfamiliar words. Textbooks, for example, have glossaries, often with the words in bold. It won’t always be apparent that this is how they work, unless pupils are taught. Appositives, where a noun or noun phrase is immediately followed by an explanatory noun phrase, are built into some texts, particularly explanatory ones: Paleontology, the study of ancient life through fossils, provides insights into the evolution and history of organisms that lived long ago. Pupils can be taught to look for these in certain text types and in certain subjects.

What does it look like in my subject?

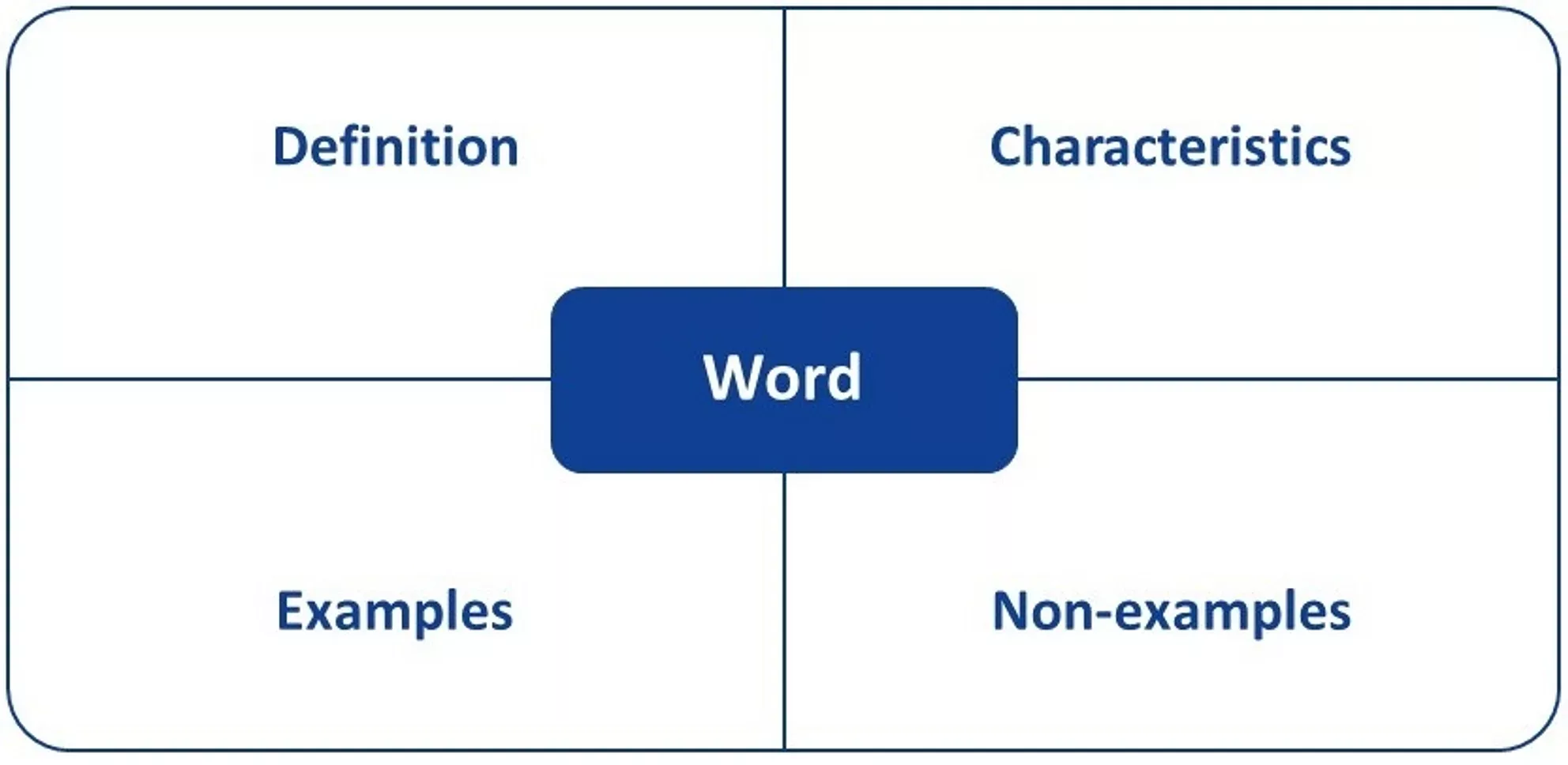

Many readers will be familiar with the Frayer Model, a method of elaborating on vocabulary.

This great blog from Alex Quigley looks at how we can adapt the Frayer Model to reflect subject disciplines. For English Literature, he chooses definition; connotations; examples; linked ideas/themes. He writes: “Does the ‘Frayer model’ alone transform understanding of words? Well, no – not really. Still, I found it a quick and handy strategy to explicitly closely analyse important vocabulary choices in English. In subsequent questionnaire feedback, numerous students commented that the model was helpful in getting them to recognise the most important ‘keystone’ words and ideas to analyse.” There is another great example for Science from Alister Talbot.

What is your version of the Frayer Model? Concept; characteristics; examples; analogies? Term; definition; cause; effect? Definition; synonym; antonym; use in a sentence?

And always ask what it looks like in your subject, not just for vocabulary, but for every aspect of literacy.

*My own footnote. ‘Bat-fowling’: the catching of birds at night when at roost by hitting them with a club. Also used metaphorically to mean swindle.

Graves, M (2008). The Vocabulary Book. Learning & Instruction. Teachers College Press.

Shanahan, T; Shanahan, C. (2013): What Is Disciplinary Literacy and Why Does It Matter?. Topics in Language Disorders 32(1):p 7 – 18,